Back Světová náboženství Czech ادیان جهانی Persian Wrâldreligy Frisian Agama-agama dunia ID សាសនាសកល Cambodian जागतिक धर्म Marathi Religiões mundiais Portuguese World religions SIMPLE Zvinamato zve pasirose Shona Jahon dinlari Uzbek

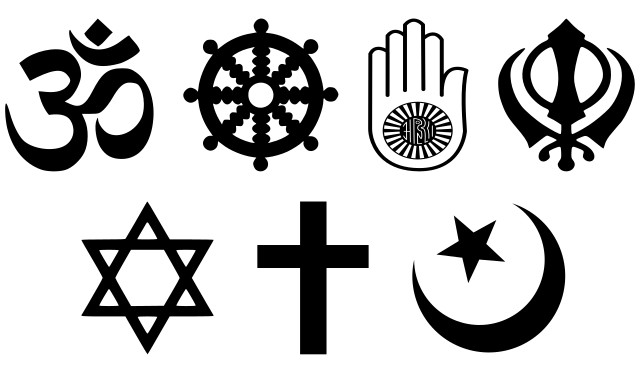

Symbols commonly associated with six of the religions labelled "world religions:” clockwise from the top, these represent Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism, Judaism, and Christianity, and Islam.

Symbols commonly associated with six of the religions labelled "world religions:” clockwise from the top, these represent Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism, Judaism, and Christianity, and Islam.

World religions is a category used in the study of religion to demarcate at least five—and in some cases more—religions that are deemed to have been especially large, internationally widespread, or influential in the development of Western society. Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, and Judaism are always included in the list. From a perspective of theological objectivity and totality, inclusion of other religions in the category, such as that of Sikhism, and to lesser degree, Shinto is too observed.These are often juxtaposed against other categories, such as folk religions, Indigenous religions, and new religious movements (NRMs), which are also used by scholars in this field of research. Less dividing is the concept of major religious groups.

The world religions paradigm was developed in the United Kingdom during the 1960s, where it was pioneered by phenomenological scholars of religion such as Ninian Smart. It was designed to broaden the study of religion away from its heavy focus on Christianity by taking into account other large religious traditions around the world. The paradigm is often used by lecturers instructing undergraduate students in the study of religion and is also the framework used by school teachers in the United Kingdom and other countries. The paradigm's emphasis on viewing these religious movements as distinct and mutually exclusive entities has also had a wider impact on the categorisation of religion—for instance in censuses—in both Western countries and elsewhere.

Since the late 20th century, the paradigm has faced critique by scholars of religion such as Jonathan Z. Smith, some of whom have argued for its abandonment. Critics have argued that the world religions paradigm is inappropriate because it takes the Protestant branch of Nicene Christianity as the model for what constitutes "religion"; that it is tied up with discourses of modernity, including the power relations present in modern society; that it encourages an uncritical understanding of religion; and that it makes a value judgment as to what religions should be considered "major". Others have argued that it remains useful in the classroom, so long as students are made aware that it is a socially-constructed category.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search